Written by Juan Pablo Toledo Hormazabal

For many years, I heard about global warming and climate change but the threats always seemed so distant and I was not conscious of the dangers close to me. Only in the last few years did I start to worry about it.

Since my awakening, I have been trying to tell people about the climate problem but soon I realized how difficult it is. Of course, communicating the climate emergency is difficult everywhere but in Chile it is difficult in two special ways. First of all, you have to communicate climate hazards of 30 years in the future to people that deal everyday with problems like lack of health care or food. This problem is common in less developed areas of the world. Then there is a second difficulty which is felt particularly acutely in Chile and other countries with a lot of extractivism. This is that various organizations as well as an important segment of the population are already radicalized against extractivism and are convinced that most of the environmental degradation is because of extractive companies. They often see climate change as another excuse that large corporations use as a shield to hide their responsibility for environmental degradation. One of the most popular slogans of Chilean environmental organizations is “No es sequía, es saqueo” that means “It’s not drought, it’s pillage.” So, in the north of Chile, you hear “It’s not drought, it’s the avocado industry.” In the central region you hear “It’s not climate change, wild fires come from the timber industry.” And in the south, they say “It’s not climate change, algae blooms are because of salmon farming.” You cannot blame them. Such reactions are the result of decades of conflict between local communities and the abuses of irresponsible companies enabled by poor environmental regulations.

So, when I thought about how to raise awareness of the problem in an easy way, I realized that the best idea for the Chilean context is to tell people the risks and opportunities of global change as it relates to their particular reality and territory: village to village and house to house, constantly highlighting that the global problem is yet another reason to fight against local exploitation of nature and theft of natural resources. At that moment, the Pongo project was born. I chose the word Pongo because Pongo, or the orangutan, is for me the symbol of the poorest people in the world who contemplate the destruction of their environment and, at the same time, suffer the consequences of climate change.

During the first months, I found many scientists and young students eager to communicate what they knew about the global emergency. Although it was difficult to find interested organizations, we held several programs which had a lot of participation and were widely accepted.

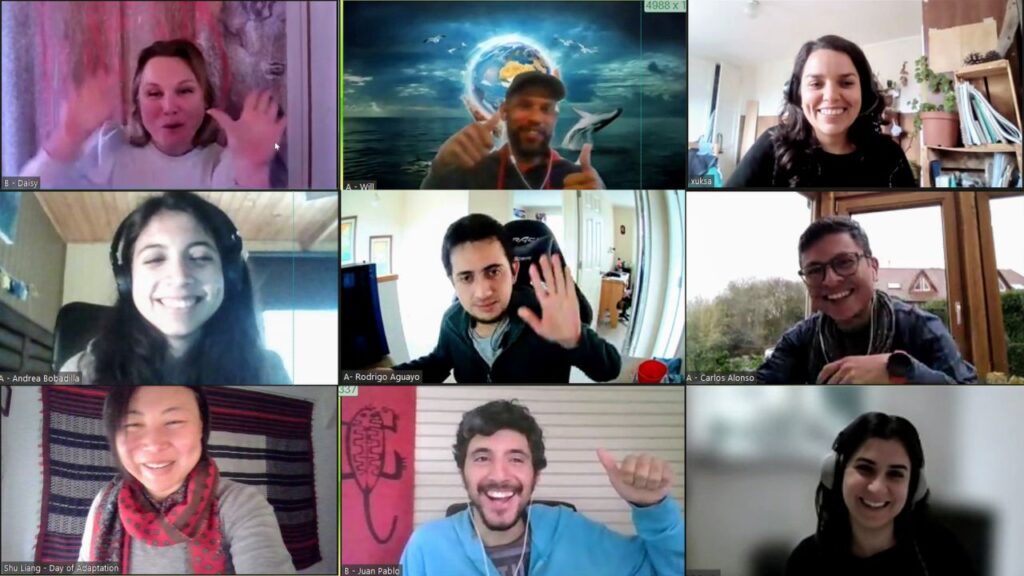

In that context, I found “Minions of Disruption” on social media and I was surprised that there exists a board game about the climate issue. I was also surprised and pleased at how receptive Day of Adaptation was, and how easy and fast it was to set up a Game Day for Pongo. At the end of each meeting, I really felt that we were together in the same fight, albeit on different sides of the Atlantic. That feeling of community really helps me to bear the stress and the anxiety that I feel when studying climate change.

When I started the game, the board’s range of colors and illustrations immediately caught my attention and pulled me in. Once I chose my token and started the game, I felt like I was in a city which is trying to adapt to very aggressive and quickly developing climatic changes. I was able to recognize different sectors of the society such as education, health and industry, and how they face problems related to temperature or precipitation. It was exciting to alleviate those problems through the implementation of environmentally-friendly solutions. There is a budget for everything and the game shows that very well because all the solutions cost resources from a common pot that all players use. This feature of the game is particularly valuable because it leads to a very rich discussion about what is the best way to invest the resources. All this occurs while more emissions are being released into the environment which intensifies climate change’s disruptive effects.

I am grateful for the opportunity to play the game and to connect with the climate leaders from Day of Adaptation. I also really think that this game will help people in Chile to become aware of the emergency and at the same time give some innovative ideas of how to deal with the problems that the changing climate creates.

About the author: Juan Pablo is founder of Pongo, Contra los efectos humanitarios del cambio climático. He is a 27 year-old Chilean biotechnologist and activist based in Concepción, Chile, fighting against the terrible effects of extractivism, pollution and deforestation in Chile.