“When I played the game, I’m going to admit it out loud for the first time, I cheated […] being involved in your game revealed parts of me that I did not know were there […] There was a kind of ‘Oh this is a game, it’s fun’, and also there was a part of me that really did not want to lose.”

This reflection – one of the many insightful commentaries by the Deep Adaptation network – hits the mark describing how game elements can trigger unexpected emotions within us. Inspired by this podcast joined by the founder of Day of Adaptation (DAYAD), Shu Liang, this short article lays out our journey to the discovery of how emotions can be channeled through gamification in order to stimulate collective climate action.

Games are not only fun

The most common way players describe Minions of Disruptions is simply “fun”. While this is, without a doubt, what motivates the DAYAD team to get up in the morning, there is a backside. Namely, the frequently revisited concern also raised in the podcast, if fun is yet another way to deny our need to change?

This concern is understandable as humor is a well-known defense used to suffocate difficult thoughts. However, the game experiences with Minions of Disruptions have shown us repeatedly that the opposite is also possible. Namely, fun can function as a vehicle to enter the realm of self-observation and transformation.

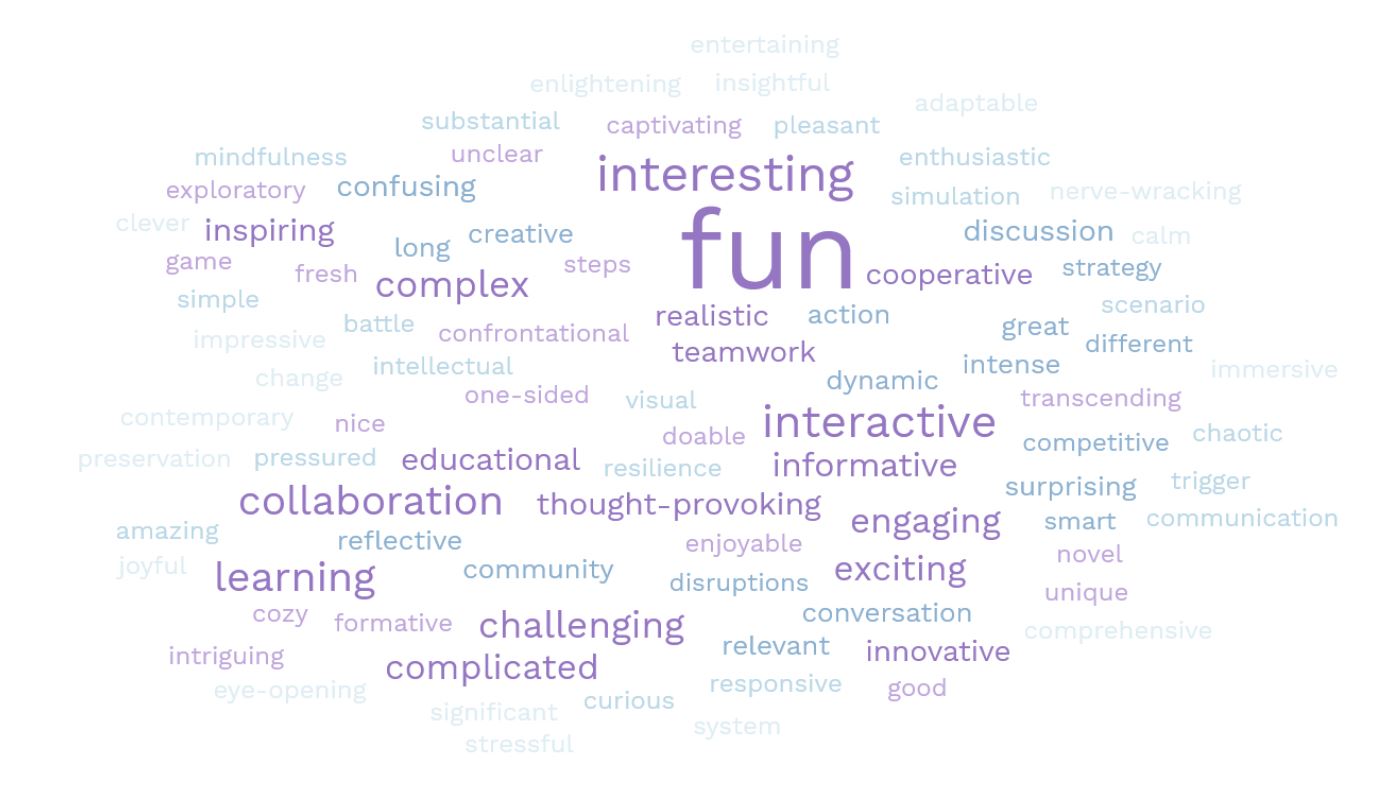

While fun is the most used keyword to describe the Game Day experience, our data analysis suggests that several layers of thought are provoked by Minions of Disruptions.

Since 2019 we have asked participants from more than ten Game Day events to share their experience in a survey or interview format. From the reactions of 80+ participants, we have detected a trend, where jokes, laughter, and fun social interaction are continuously referred to as a critical entry point into heavier topics.

This finding is depicted in the picture above where, next to fun, the game experience is being described among other things, as thought-provoking, interesting, and informative. This has brought us the realization that we are in the business of making fun serious!

Serious fun through feelings of overwhelm

Serious games, such as Minions of Disruptions, are made with the intention to communicate about a serious topic, using playfulness as the means to an end. The challenge, however, is to turn this intention into actually engaging audiences. After three years of experimentation, however, we are starting to understand that creating a space where participants can experience a range of emotions is also what triggers personal reflections on adaptation.

For example, Katie Carr, the podcast host, describes her game experience as frustrating. This frustration within her mounted to a degree that she decided to cheat at the game. These emotions are mirrored by some other participant accounts describing their experiences as chaotic, nerve-wracking, and a little overwhelming.

In the first instance, a game causing emotions of overwhelm does not seem conducive to empowerment. However, reading between the lines, an incentive to cheat can be seen as having a deep engagement to the game and the cause. In line with Wu and Lee’s findings, this shows how the game becomes an intrinsic motivator; not a boring session you have to attend, but a challenge you must overcome.

The gist of Minions of Disruptions is the storyline that increases pressure to act gradually while allowing enough time for team dynamics to form. Another aspect is the roleplay. When players take up the roles of activists in a community or an organization – Zillians – they start making decisions like one.

Studying the reactions of players, we have seen how passion and imagination make a group of strangers grow from a hesitant group facing difficulties into a strategizing and collaborative unit. Sometimes this experience is so powerful that the effect spills over. In the post-game debriefings, some players connect the game to their own organization or community, and start asking themselves what should change.

Gamification creates space for action

Shu Liang argues in the podcast, that if the climate movement is seen as “doomist”, the general audience feels more fear than actual motivation to act. While it is true that Minions of Disruptions simplifies reality and makes climate technicalities seem easy, this simplification may be just what is needed to engage more people.

As long as climate change is approached only through a heavy realist narrative, it is no wonder that many individuals would rather ignore the messages they receive. When no solution space is actively created, there is also no intrinsic motivation to understand, accept nor commit to climate action.

In the real world, it is not possible to cheat your way into adaptation. Nevertheless, gamification can be used to unpack information and gradually introduce ideas in a non-threatening way. We see this as a bridge to more complex and difficult discussions.

One of the Game Day participants argues in an interview that adaptation “happens at the table when people are talking […] It doesn’t need to be expressed on the board game”. Three years into our journey, we are starting to witness the power of gamification as playfulness that creates space for communities and organizations to reflect their agency in climate action. Moreover, we believe that the psychological side of adaptation should not be forgotten.

George Marshall writes in his book “Don’t even think about it – why our brains are wired to ignore climate change” about the psychological challenge of changing behavior. One of his conclusions is that communication around climate change is often too technical and attributes inaction to a lack of plans, while the real obstacle may in fact be emotional.

To make action possible, we all need to connect with our emotions – whether fear or frustration. In a simulated reality, we feel safe enough to explore and connect to those feelings on the one hand, and we are able to channel them through discussion in our community or organization on the other hand. And if we leave the session feeling like we had serious fun doing so, taking the next steps seems so much easier.

Stichting Day of Adaptation thanks Deep Adaptation Forum and Katie Carr for the podcast opportunity. You can check out the full Q&A with Shu Liang on the Deep Adaptation Forum with Katie Carr here:

References:

Marshall, George. (2014). Don’t even think about it – why our brains are wired to ignore climate change. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc.

Wu, J.S. and Lee, J.L. (2015). Climate change games as tools for education and engagement. Nature Climate Change, vol. 5.

About the author: Minja Sillanpää is a Master student of Disaster Risk Management and Climate Change Adaptation at Lund University, Sweden. Together with other colleagues at DAYAD, she is conducting research on the effectiveness of Minions of Disruptions as a tool of climate communication.